This article originally appear in the book “Murder & Mayhem In Rockford Illinois” By Kathi Kresol.

Camp Grant was built in 1917, at the southern edge of Rockford Illinois, covered over five thousand acres, included over 1,100 buildings, and at its height housed over fifty thousand men. It was used as a training center for cavalry, machine gunners, engineers and artillery personnel during World War I. After the war, the camp was used for a variety of purposes, including as a temporary training facility for the Illinois National Guard.

In 1925, a very special training was planned, and the camp was expecting the largest number of soldiers since the end of World War I. Preparations for the huge encampment that took place in August 1925 had gone on for months. New mess halls and latrines were built, and other buildings were renovated. The Illinois National Guard units were expected to meet and conduct maneuvers at the camp from August 15th through August 29th.. Over eight thousand men were expected at the camp during that period.

City officials and the National Guard were expecting big crowds for the training. They had prepared for ten thousand visitors from all over northern Illinois. There was a variety of military maneuvers planned for the special training, including chemical warfare and artillery including howitzers and machine guns. All did not go according to plan.

On Sunday, August 24 1925, the training was to include a chemical warfare demonstration in the afternoon. Hundreds of cars containing civilians lined the field to watch the demonstration of simulated battle maneuvers. The gunners were laying down a smokescreen for a line of infantry when a volley of phosphorous gas smoke grenades exploded and came down in the midst of the spectators’ cars.

One newspaper reported the event: “One of the bombs exploded right on top of a car owned by Gary Flanders. The bomb tore its way down through the car roof and exploded directly onto Flanders and the other people in the car: The smoke from the grenade was so thick that even cars around the Flanders’ car were engulfed. The horrific scene was made worse by the sound of the children crying and screaming. Flanders exited his car and went running through the smoke with his clothing on fire. A soldier grabbed Flanders and threw him to the ground. The soldier rolled Flanders around until the flames were extinguished.”

Another bomb hit the running board of John Anderson’s car where his wife and three children sat. When the bomb exploded, it blew out the windshield and burned Anderson on his face and neck.

E.C. Hayes and his five-year-old son were injured when the boy’s clothes caught on fire. E.C. picked up the boy and ran to safety and then tore the child’s clothes off. Unfortunately, the child suffered severe burns on his head, and his father’s hands and arms were burned.

Camp ambulances rushed the injured to the camp hospital. Over seventeen people were injured from the grenades, mostly children. Over five thousand people were watching the military maneuvers on Sunday, and Major General Milton J. Foreman, commander of the Thirty-third Division, promised a thorough investigation into the accident. The newspaper also mentioned that only those spectators who crossed the guard line had been injured.

The war games continued the next day to an even more horrific event. The Eighth Infantry unit was demonstrating a type of cannon called a howitzer when it exploded during the battle drills. The accident occurred on the gun range below the Camp Grant Bridge over the Rock River. There were fifty-five men in the unit, and thirty-eight of them were wounded. The Eighth Infantry unit was part of the first all-Black National Guard Regiment. Seven men from the Eighth Infantry were killed immediately, two more would die later and thirty-one other men were wounded.

A list of the dead includes

• Captain Osseola A. Browning; Chicago. Illinois. He was the commander of the howitzer company. Osseola had both legs shattered and one torn off. and his chest was caved in.

• Corporal Henry Williams; Chicago. Illinois. He was in charge of the gun squad.

• Private Delmas Campbell; Chicago. Illinois.

• Private Herbert Durand; Chicago, Illinois.

• Private Benny Anderson; Chicago, Illinois.

• Private Charles Wright; Chicago, Illinois. Died at Swedish American Hospital at 1:30 p.m. His leg had been torn off, and he had a broken arm.

• Private Elmo Baynes; Chicago. Illinois. Twenty years old, he died at the Rockford Hospital at 2:25 p.m. on the operating table.

• Private Todd Moseley; Chicago, Illinois.

Several people were severely injured, including little Alan Williams, an eight-year-old boy who had his arm blown off. He was the nephew of Captain Browning and considered the “mascot” of the howitzer company. Little Alan was the only civilian near the howitzer when it exploded.

Medical units from the camp were sent immediately by Major General Milton Foreman. The injured men were brought to the camp hospital, and then the more severely wounded were delivered to Rockford’s three hospitals.

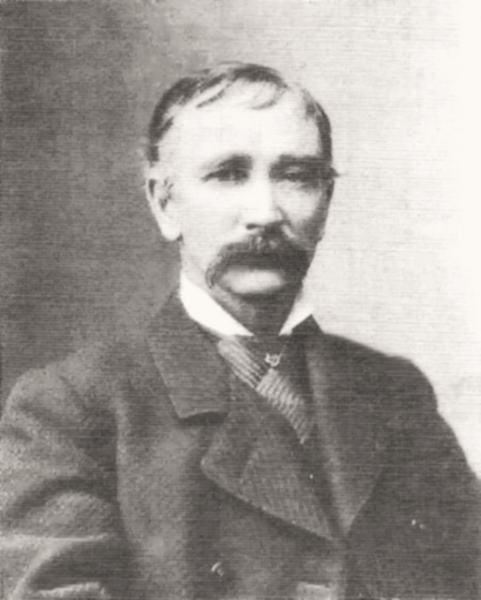

Captain Osseola Browning was a war hero and the pride of his unit. He was a lieutenant in the 370th Infantry during World War I. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre for bravery in action by the French government.

Tragically, his wife had arrived in the camp to spend the day with her husband. She collapsed after hearing of the death of her husband and was rushed to the camp hospital herself.

Browning was born in Chicago on June 18, 1896. He graduated from Wendall Phillips High School in 1914 and went on to study chemistry at Northwestern University. He attended arsenal machine gun school at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, in 1916 and the Infantry School of Arms at Camp Logan in Houston. Browning went to the First Corps School in France and served there with distinction during World War I. Osseola took great pride in serving in the howitzer division.

Stanley Jones, department sergeant, was delivering a truckload of shells when the explosion took place. Jones heard Captain Browning order Corporal Williams to fire the mortar. Jones was hit with a deafening blast that knocked him down. The next thing he felt was the body of one of the men killed in the blast landing on top of him.

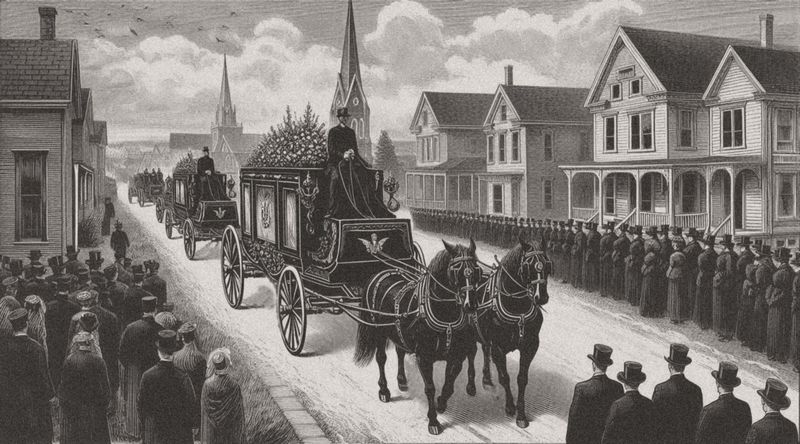

The bodies of the dead soldiers were transported to the Cavanaugh and Cannon Funeral rooms on South Court Street. Coroner Fred Olson did not conduct a civilian inquest but did attend the military one. The commander of the Eighth, Colonel Otis B. Duncan, arranged for a funeral service in Chicago at the Eighth’s armory.

Witnesses described the scene: “The men of the ill-fated grouped about him [Colonel Browning] as he explained the workings of the instrument of death he was demonstrating. The load was inserted. The men stepped back a few paces, and Captain Browning ordered Corporal Williams to prepare to fire. Corporal Williams dropped shell into the mortar.”

Huge chunks of metal flew through the air, lore off limbs and penetrated stomachs and chests. The screams of the dying and wounded could be heard throughout the smoke-filled field.

Another nephew of Captain Browning, Rush Smith, ran and walked the miles front the field to the camp to fall at the feet of Master Sergeant Leon Cornick to tell him of the tragedy. Leon swept the boy into his arms and carried him to his tent. Rush sobbed as he told the tale of his “Uncle Os” and the other men being “blown to pieces.” Later, the scene between the little boy and the newly widowed wife of Osseola was heartbreaking to all who witnessed it.

A witness of the scene, Private James Hasty, came close to being another victim of the bombing. A piece of metal tore through his coat sleeve and embedded in the canteen that hung at his side. The hole it ripped into the canteen was over two inches in diameter.

A memorial service was held for the men at Camp Grant. The newspapers called it “a sacred service to the memory of the victims of the worst disaster that has ever taken place in Camp Grant since its inauguration as an army cantonment.”

Days later, a larger memorial service was held in the sport center of the Eighth Regiment in Chicago. Captain William S. Bradden spoke a moving eulogy to the men, who gathered to honor their fallen comrades.

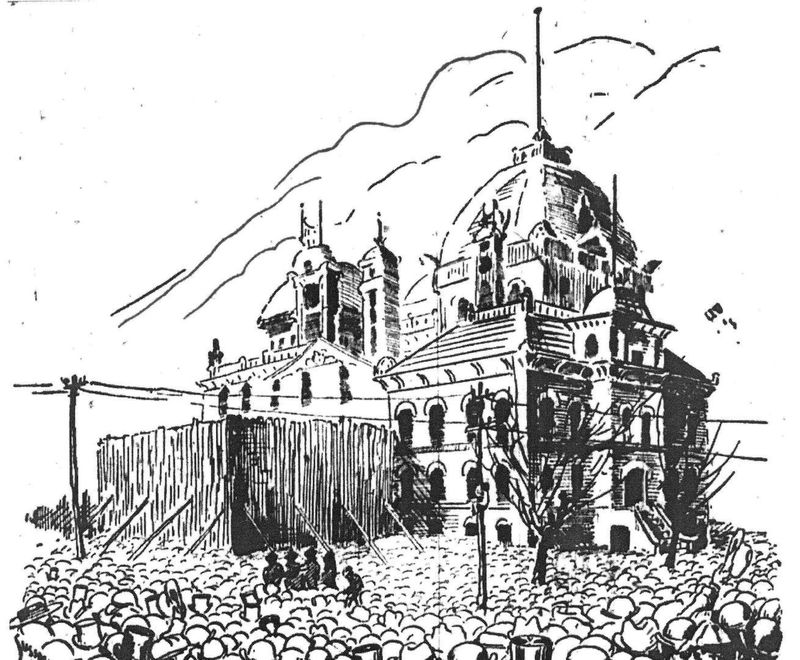

Thirty-five thousand people jammed the Eighth Infantry armory for the memorial service on September 1. A guard unit was sent from Rockford. Buckbee Greenhouses designed a floral arrangement, and the citizens of Rockford donated money for the floral arrangement in a bucket drive. It was in the shape of a giant howitzer. The arrangement was five feet tall, and the barrel was seven feet long and carried a sign that stated. “Sympathy from the Citizens of Rockford.” It was made from red, white and blue flowers and weighed over 250 pounds. Major General Milton J. Foreman, commander of the Thirty-third Division, and Colonel Otis Duncan, commander of the Eighth Infantry; also attended the services.

Rockford judge Carpenter spoke for the 100,000 people from Winnebago County who sent their respects to the families of the dead men.

There was not a dry eye in the building when taps was played. The caskets were open as the families and friends filed past. The bodies were laid out in state under military guard Sunday night and were released to the families for burial the next day.

Even during the memorial service for the dead soldiers, other soldiers were still in Rockford hospitals fighting for their lives. One, Lieutenant F.G. Harris, had his abdomen punctured by a large piece of flying shrapnel and suffered a relapse at St. Anthony Hospital. His mother and his wife traveled to his bedside.

On September 12, the remainder of the seven wounded infantrymen were moved from Rockford hospitals and delivered home to Chicago. First Lieutenant H.A. Callis of the Eighth Infantry Regiment, medical detachment, would accompany the soldiers back to Chicago. Fortunately, Allan Williams, the little eight-year-old mascot of the Eighth, survived and returned to his school.

Major General Milton J. Foreman stated in his tribute to the fallen soldiers, “Not alone on battlefields are heroes found.” He emphasized the sacrifice that the eight men made while serving in the Illinois National Guard.

Copyright © 2015, 2025 Kathi Kresol, Haunted Rockford Events